The success of Operation Exodus prompted many community members to promote more community control of the schools, because reform within BPS seemed unlikely. Community control meant many things, including naming neighborhood schools, greater presence of black administrators, and enlarged roles for parents in school development.

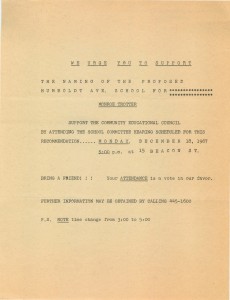

One of the first battles of community control came up at Patrick T. Campbell Middle School (which would be eventually changed to Martin Luther King Middle School). The school was statistically one of the worst performing in the entire system, and attempts by administrators to fix the school had been stymied by the Boston School Committee. Data compiled by the Boston School Committee and NAACP proved that students were receiving an inferior education. Operation Exodus started the King-Timility Coalition, which demanded that a black principal be hired and that the school be closed for a week so that the whole school could be overhauled. This attempt was unsuccessful but showed an important shift in the demands of the community.

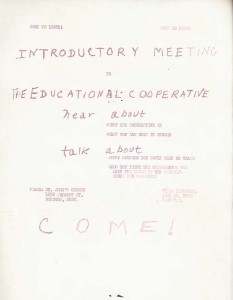

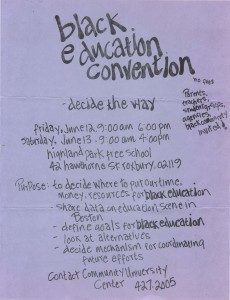

Community control also meant exploring new forms of educational and pedagogical practices, as had been done with Freedom Schools. Groups started holding Black Education Conventions and groups like the Educational Cooperative met to share resources and strategies.

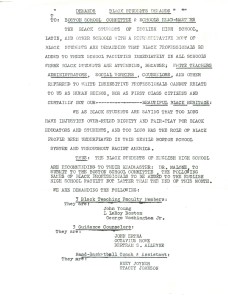

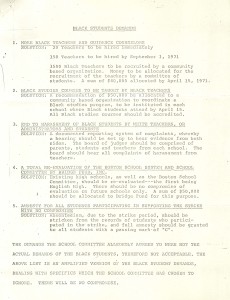

In 1971, students began striking at Boston English High School to protest unfair treatment of black students, showing they too were creating a bigger voice for themselves in their education. The student demands are below in various forms. When the NAACP was arguing their case in 1974, leader Ellen Jackson argued that by then, black students made up one-third of the BPS system but black leadership role in the schools remained miniscule.