Boston’s history of civil rights and education reform might make it surprising that Boston became a battleground around de facto segregation. De facto segregation results from factors other than segregation laws.

After World War II, educational quality and funding decreased in Boston, and the first victim was commitment to equality. The city’s demographics changed, affected by both “white flight” in response to the Northern migration of blacks from the South and the general move to the suburbs in the 1950s.

Neighborhoods tended to be racially isolated and homogenous, despite the city’s relative diversity. In 1963 the Boston School Committee received a report from the Education Committee of the Boston Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that showed that blacks were economically depressed and ghettoized by racist hiring and housing practices.

Although many people had suspected that black neighborhood schools were shortchanging students and had inferior conditions, the problems had not been formally studied. Parents saw dirty, overcrowded conditions in predominantly black schools. Through word of mouth and visits to white schools, people saw that black students did not share opportunities such as field trips, advanced classroom technology, and better learning environments. There were only 40 black teachers in the whole district and no black principals. Very few black students were being admitted to prestigious exam schools. This exhibit does not seek to prove or disprove any racial imbalance or unequal treatment for students of color, but it does describe the conditions black students and parents refer to as their experience.

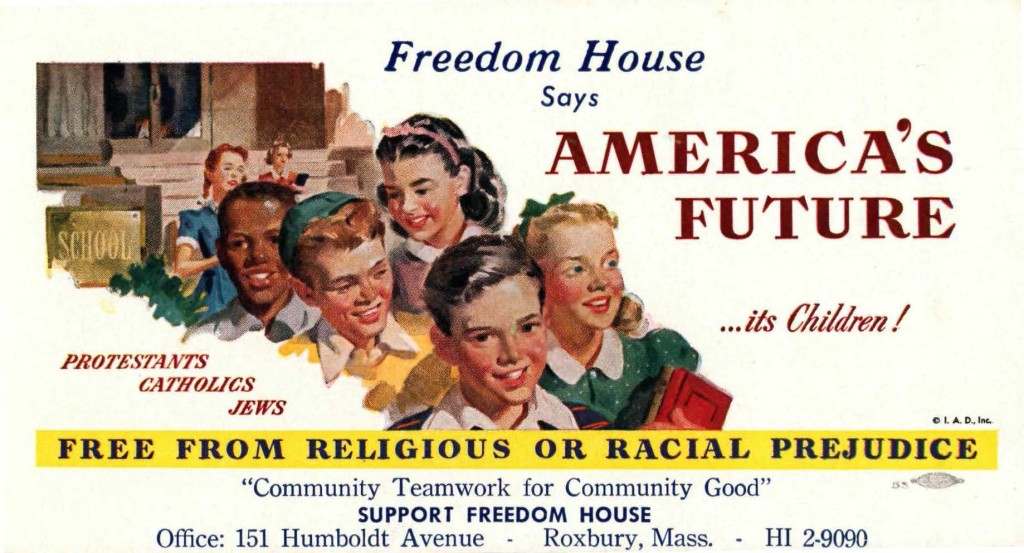

Groups formed to tackle what people saw as inferior services for black children. Many early conversations began at Freedom House, a Roxbury social services center. The Boston Educational Collective began to meet 1961. Dorothy Bisbee started the Citizens for Boston Public Schools (CBPS) around this time, and black community members Herb Gleason and Paul Parks quickly joined. The Boston Chapter of the NAACP already had an Education Committee advocating for black college students. However, as conversations grew, the Committee redirected its focus on Boston Public Schools (BPS).

As more voices began to call for change, CBPS prepared a study to describe the true state of Boston schools, but BPS refused to provide data. However, alarming statistics were found through the CBPS survey and other studies by the NAACP. The studies indicated that BPS was gerrymandering school districts, seeming to separate races rather than following logical boundaries. Over 7000 black students attended 14 elementary schools and one junior high that were over 90% black. Another 6000 attended 12 elementary schools and 2 junior highs that were 50-85% black, despite being in a city that was 15% black. Of the 13 schools in predominantly black neighborhoods, only one school had been built since 1933, two more built after 1913, ten built before 1913, two of which were almost 100 years old. Four had been recommended for renovation or condemnation. Compared to white districts in the BPS system, these schools had a 2–20% lag in instructional expenses and 11–27% lags in health services.

In the early 1960s the NAACP and others met with administrators who were reluctant to fix the problems. One principal chalked up performance differences as “negroes do not make their kids learn.” Superintendent Gillis refused to recognize de facto segregation in a March 1962 meeting with the Education Committee. School Committee member William O’Connor allegedly said, “We have no inferior education in our schools. What we have been getting is an inferior type of student with which we have to cope. It’s a difficult problem.”